🐙 Shinmei Children’s Park – Home of the Tako Slide

🏞️ A Playground with Local History

Shinmei Jidō Yūen (神明児童遊園) is a beloved local park in Futaba, Shinagawa, best known for its iconic red octopus-shaped slide. The park first opened in 1964 and gained popularity in 1968 when a large, hand-crafted “parent” octopus slide and a smaller “baby” octopus were installed. It quickly became known to locals as “Tako Kōen” (“Octopus Park”).

🐙 The Original Octopus Slide

The original large octopus slide (about 4.5 meters tall, 10 meters wide) was crafted by artisans at Maeda Outdoor Art Co., Ltd (前田屋外美術株式会社), featuring a smaller companion octopus nearby (about 1.5 meters tall). This unique “parent and child” design was first introduced in Shinagawa. Since the 1960s, over 190 octopus slides in parks all over Japan but this is believed by many to be the first one of its kind.

🌟 From Playground Legend to Pop Culture Icon

The park’s octopus slide became even more famous after appearing in a 1996 NTT DoCoMo pager commercial starring actress Ryoko Hirosue, becoming a touchstone of nostalgia for many.

🔧 Renewal and Community Farewell

In 2007, redevelopment and roadworks closed the playground. Locals wished to move the original octopus slide, but safety checks found severe internal rust. The large octopus was demolished, but not before a heartfelt farewell event—children decorated it with flowers, sang songs, and played on it one last time. The “baby” octopus was saved and moved to the new site.

✨ A New Octopus for a New Park

When the park reopened in 2010, a new, large octopus slide was built in the same spirit as the original, with the preserved “baby octopus” climbing equipment beside it. The park today is divided by a main road, with playground equipment and open space on both sides, next to Futaba Library.

🎠 Play Equipment & Park Features

- Large octopus-shaped slide (2010, recreating the 1968 original)

- Small “baby octopus” (original, moved after demolition)

- Open play areas, benches, and shade trees

- Park divided by Tokyo Metropolitan Route 26; next to Futaba Library

🧭 Visitor Information

Address: 4-4-13 Futaba, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 142-0043

Opening hours: Open 24 hours (limited lighting at night)

Admission: Free

Facilities: Playground equipment, benches.

Official Info: Shinagawa City (2007) – Octopus Slide and Farewell

🧭 Where is it?

| what3words | ///sheep.gaps.jigging |

| latitude longitude | 35.608569, 139.726592 |

| Nearest station(s) | Shimoshinmei Station (Oimachi Line) |

| Nearest public conveniences | The station or the Lawson right next to it. |

Show me a sign.

There’s a sign at the pointy end of the small park.

Withervee says…

When I first saw the tiny park with the red octopodes outside Shimoshinmei station I couldn’t see anything special about it. The nearby Shinagawa Central Park is much bigger and has far more facilities. And, there is a much larger Whale slide at Higashi-Shinagawa Marine Park.

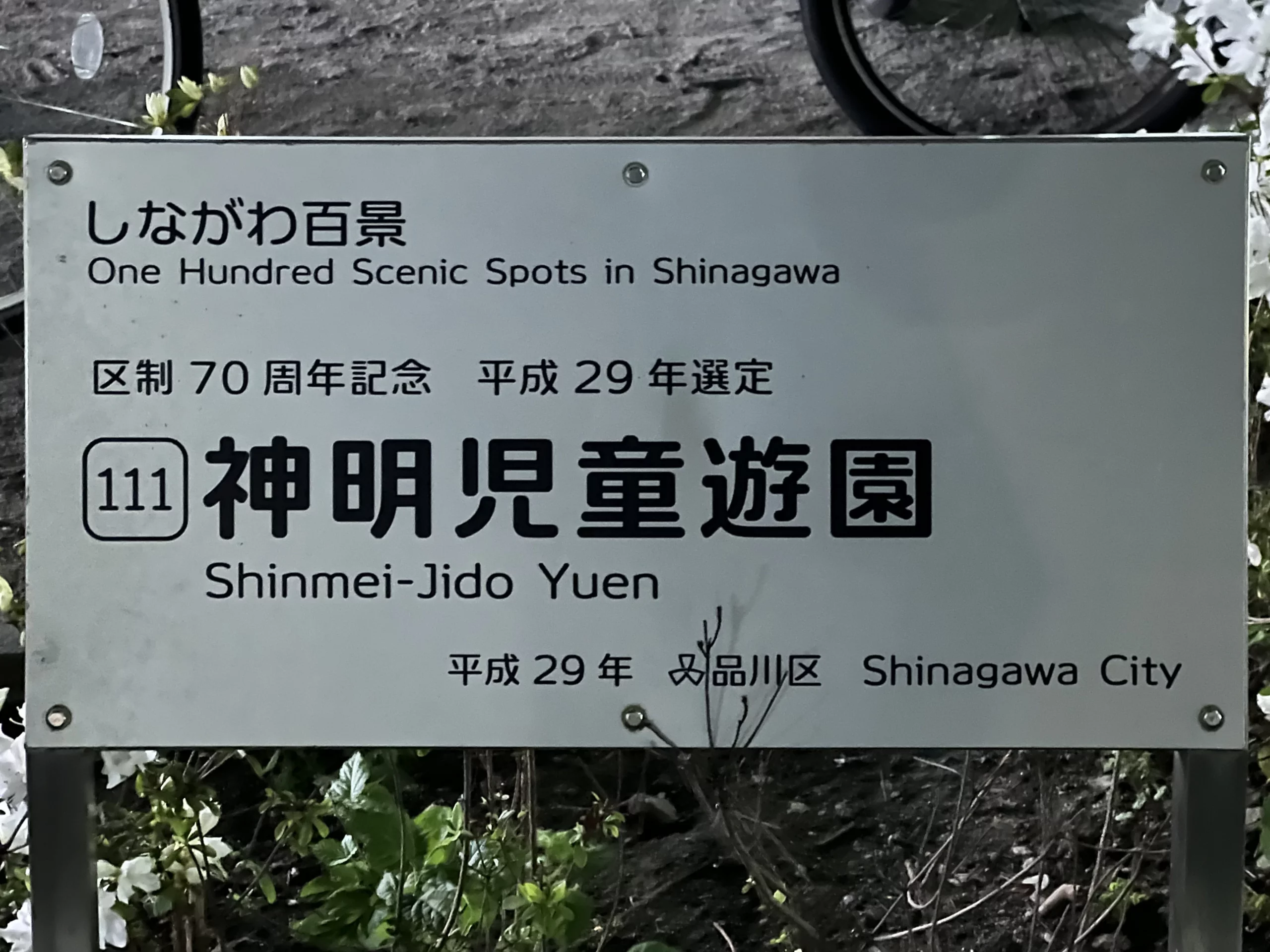

So I investigated further. Looking at the 1996 video the park was much bigger that it is now before the . As seen in this frame from the NTT Docomo pager commercial.

And, in this aerial map of you can see how the park changes size between 1990 and 2000’s after the road build.

🐙 Playground Legends & Legal Drama

🎨 How the Octopus Slide Was Born (By Accident)

Why so many octopus slides in Japan? Controversially ,Some people say the trend didn’t start in Shinagawa at all!

Reportedly, it all started in Adachi Ward, 1965, when sculptor Ken Kudo (工藤健) designed a surreal “Stone Mountain.” A city official asked: “Put a head on it—make it an octopus!” The first tako slide became a hit and orders poured in. Kudo later said the “head” turned it into a magical hideout for children. Today, more than 200 can be found in Japan, with Shinagawa’s 1968 “parent and child” version inspiring many.

⚖️ Court Battles Over Playground “Art”

The story of the octopus slide also became a Japanese legal drama. The original slides were produced by Maeda Kankyo Bijutsu (Maeda Outdoor Art) (前田環境美術), a Tokyo-based company and one of the first to build and popularize octopus slides from the late 1960s onward. For decades, Maeda slides—often modeled on Ken Kudo’s influential designs—appeared in parks across Japan. This company was dissolved at some point. Maeda Kankyō Bijutsu (Maeda Environmental Art) (前田環境美術) inheriting the intellectual property rights.

Mollusc Themed Play Object Competitors Enter the Arena

However, as octopus slides spread, other companies began making similar playground equipment. One such company was ANS (アンス株式会社), which employed several former Maeda designers and directors. Disputes over the originality of the design and client lists grew over time.

The first major legal fight began in 2011, when Maeda Kankyō Bijutsu sued ANS and several individuals. Maeda alleged that former employees of Maeda, now working for ANS, had improperly used Maeda’s confidential business information and designs to win contracts for similar slides in Tokyo. Maeda also claimed damages for unfair competition and breach of contract. However, the Tokyo District Court and then the Intellectual Property High Court (Tokyo, 2014) rejected all of Maeda’s claims—finding no sufficient evidence of trade secret misuse, improper competition, or contractual breach.

[Tokyo High Court 2014 Ruling]

Ding Ding – Round Two

In a separate but related copyright battle, Maeda Kankyo Bijutsu filed another suit in 2019, again targeting ANS. This time, Maeda claimed that ANS had directly copied the unique artistic design of the octopus slide—arguing that the slide should be protected as a work of art under Japanese copyright law. ANS countered that playground equipment is designed first and foremost for play and safety, and thus is not an “artwork” eligible for copyright.

In 2021, the Tokyo District Court again ruled against Maeda. The court acknowledged that the slides are visually creative but ultimately determined that the shapes and forms were “utilitarian” and dictated by function—not by artistic originality alone. The Tokyo High Court and Supreme Court both upheld this verdict in 2022, confirming that the classic octopus slide, however iconic, does not qualify for copyright as a work of art.

[Yomiuri Shimbun, 2022/08/01]

The Verdict

Octopus slides remain a shared legacy in Japan’s public spaces—free for any company to design and build, as long as safety standards are met. For many, the real value lies in the joy and memories they create, not in the courts.

[Tokyo High Court 2014] | [Prof. Kudo Interview, 2022] | [Copyright Verdict, 2022]

🐙 The Octopus Slide Boom

From Kudo’s 1965 quirky design (originally “Stone Mountain”) to the “add a head!” command, or the Shinagawa Shimoshinmei Park pairing, the octopus slide became a hit. Adachi Ward is called the “holy land” of octopus slides, but Shinagawa’s 1968 version also inspired many.

Now I get it. I imagine many people hold fond memories of the original park and the original octopus (tako) slide hence its inclusion in the 100.

Site Character

- Lifestyle 生活 (Seikatsu): ✔️

- Historical Significance 歴史 (Rekishi): ✔️

- Atmosphere/Natural Features 風土 (Fūdo): ✔️

Who in their right mind would vote for this?

- Local Generation-X and Millenial Residents

- Reminiscing commuters

- Local history buffs

- Park-bench poets

- Copyright litigation lawyers

Further Info

Octopus Mountains – Wikipedia (Japanese)

Maeda Environmental Art (archive.org web pages – Japanese)