⚔️ Sakamoto Ryōma: A Young Samurai at the Crossroads

Sakamoto Ryōma (坂本龍馬) is one of modern Japan’s most admired historical figures. He was a visionary who helped dismantle the Tokugawa shogunate and open the way for the Meiji Restoration. Yet here in Shinagawa’s Tachiaigawa district, you will not find a statue of Ryōma brandishing a sword or striding forward in boots. Instead, you will find a quietly reflective young man in straw sandals, standing still at the edge of change.

The statue, erected in 2010, shows Ryōma at about twenty years old, long before he became famous. At that time, he was stationed in Shinagawa as part of Japan’s coastal defence. He was a junior samurai from the Tosa domain, far from home and not yet sure of his path. This early moment in Ryōma’s life rarely appears in dramas or textbooks. Yet it marked the beginning of a journey that would reshape the nation.

By choosing to honour Ryōma’s youth instead of his later legacy, the statue invites visitors to connect with something quieter and more personal. It captures the feeling of standing at a crossroads, unsure of what comes next. Surrounded by the calm of an urban park, near Tachiaigawa Station, this modest site offers a chance to pause. It invites us to imagine the young samurai who once stood here, looking out toward a very different Japan.

👦 Early Life and Samurai Training

Sakamoto Ryōma was not born into greatness. His journey began in the Tosa domain on Shikoku Island, far from the centres of power in Kyoto and Edo. Born in 1836 to a low-ranking samurai family, Ryōma came of age during a time of growing tension; foreign ships loomed off Japan’s coasts and the rigid Tokugawa order showed signs of strain. His early years shaped not only his character, but also his sympathy for outsiders and his eventual break from convention.

Ryōma’s Childhood in Tosa

Ryōma was born in Kōchi, the castle town of Tosa, to a samurai family of relatively humble means. Although they had samurai status, the Sakamoto family were not of the elite warrior class, but rather merchants who had purchased their rank. A social distinction that lingered in the strict class hierarchy of the time. This outsider status would shape Ryōma’s worldview, instilling in him a lifelong resentment of social injustice and exclusion.

As a child, Ryōma was known to be timid and prone to crying, earning little admiration from his peers. But his family recognized his potential and encouraged him to study swordsmanship. This path offered both discipline and mobility within samurai society. In 1853, at the age of 17, he was sent to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to train at the renowned Shijikan fencing school, operated by the Hokushin Ittō-ryū school of swordsmanship. There, away from the rigid world of Tosa, Ryōma began to grow in confidence and skill.

It was also during this period that Japan faced increasing pressure from the West. The arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships in 1853 marked a national crisis. Young Ryōma, like many of his generation, began to question the future of the shogunate. While still a loyalist to Tosa at this stage, Ryōma was absorbing new ideas about loyalty, courage, and what it meant to defend one’s country. The seeds of transformation had been planted.

⚔ The Samurai at the Crossroads: Ryōma in Shinagawa

By the mid-1850s, Sakamoto Ryōma had completed his sword training in Edo and returned to service under the Tosa domain. His next posting would bring him back to the capital. Returning not as a student, but as a coastal guard. At this time, foreign ships were entering Japanese waters with increasing frequency, and the Tokugawa government had ordered the construction of defensive batteries in Edo Bay. One of the key locations in this network was Shinagawa, including the area we now know as Tachiaigawa.

Ryōma’s role here was part of a larger national effort to guard Japan’s shores. Still a junior samurai, he was assigned to a unit that monitored coastal activity and stood ready to repel foreign incursions. While records do not describe the daily routine in detail, it is clear that these guard posts were both tense and monotonous. Typically, hours of waiting punctuated by drills and uncertainty. For a young man of Ryōma’s temperament, this period may have been as reflective as it was formative.

🌊 A View Toward Change

From Shinagawa’s shoreline, Ryōma would have looked out over the waters of Edo Bay, knowing that change was coming. The Perry Expedition had already arrived, treaties were being signed under pressure, and discontent was spreading among the domains. Though still loyal to his lord in Tosa, Ryōma was beginning to question the old order. This quiet post in Tachiaigawa placed him at the very edge of that historic shift. He was not yet a revolutionary, but no longer just a provincial samurai.

That is why this statue, located near his former posting ground, matters. It captures a moment before action, before alliances, before fame. It reminds us that revolutions begin not in glory, but in stillness: in moments when young men are asked to stand, watch, and think. Here, in Shinagawa, Ryōma stood on the threshold of history.

🌊 A Nation in Turmoil: Ryōma’s Role in the Bakumatsu

The late Edo period, known as the Bakumatsu (幕末), was a time of national crisis. For over two centuries, Japan had lived in isolation. Now, foreign powers were forcing the country to open its ports. The arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships in 1853 sent a shock through the nation. It exposed the deep weakness of the Tokugawa government. In domains across Japan, discontent grew. For young samurai like Sakamoto Ryōma, the old world no longer seemed possible. Even so, the path ahead remained uncertain.

🧭 From Loyalty to Reform

At first, Ryōma believed that Japan could be defended through traditional means. He trained in martial arts and remained loyal to the Tosa domain. However, his views began to shift. Influenced by teachers, travelers, and early reformers, he came to see that the feudal system could not meet the challenges of the age. He started to believe that Japan’s future depended on unity and openness, not isolation. This change in thinking marked the beginning of his break from both Tosa and the Tokugawa regime.

By the early 1860s, Ryōma left his domain and became a rōnin, a masterless samurai. Yet he did not drift without purpose. Instead, he acted as a quiet intermediary between reformist domains such as Satsuma and Chōshū. These groups shared a clear goal: to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate and build a new political system. Ryōma’s bold diplomacy and personal independence gave him influence. At the same time, they made him a threat to those who wanted to preserve the old order.

Ryōma rose to prominence during this period of upheaval. More than an activist he was also a thinker. He called for a national assembly, a modern navy, equal rights, and free trade. These ideas were far ahead of their time. Although he never fought as a soldier, Ryōma stood at the center of Japan’s political transformation. He connected old and new, shaped by the fierce winds of the Bakumatsu.

🏯 The Meiji Restoration and Ryōma’s Legacy

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 ended Japan’s feudal era. It marked the start of a modern state. Many figures shaped this change. Few were as pivotal or as unconventional as Sakamoto Ryōma. As a rōnin, he worked outside the system. Ryōma brokered political alliances. He challenged old hierarchies. He imagined a nation free from hereditary rule.

Ryōma helped bring Satsuma and Chōshū together. These domains had been bitter enemies. Their alliance became the key to toppling the Tokugawa shogunate. Ryōma acted quietly and on his own terms. He gave both sides a reason to work together. Their goal was simple: restore imperial rule and modernise Japan before foreign powers took control.

Eight-Point Plan

In 1867, Ryōma drafted one of the earliest plans for a modern Japanese state. His “Eight-Point Plan” (船中八策, Senchū Hassaku) outlined a vision of national renewal. It called for a representative assembly based on merit rather than birth, along with legal equality, a standing army, a navy, and the abolition of feudal class divisions. The plan also urged treaty revision, the creation of a professional bureaucracy, and the adoption of open markets.

Ryōma did not live to see these reforms enacted. Even so, many of his ideas were later adopted by the new Meiji government.

Ryōma’s legacy lies in ideas, not in power. He helped Japan move from the age of the sword to the age of the state. Instead of commanding others, he persuaded. Rather than relying on rank, he acted with imagination and boldness. Ryōma never ruled. Yet he believed Japan could change. That belief continues to define his name.

🚶♂ Sakamoto Ryōma’s Later Years and Tragic Death

By the late 1860s, Sakamoto Ryōma was known across Japan. He held no official title. But he was helping to shape the country’s future. Ryōma was now a fugutaku, a samurai with no lord. He moved between Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo. He acted as a mediator, a strategist, and a messenger. One wrong move could have meant death. His vision was clear: a unified Japan ruled by principles, not by privilege. That vision made him a threat to those in power.

⚔ The Assassination at Omiya Inn

In 1867, just months after he submitted his “Eight-Point Plan” to the imperial court, Ryōma was killed. He was only 31. The attack took place at the Omiya Inn in Kyoto, where he had sought shelter with a close ally. Armed men stormed the building and cut him down. No one ever proved who ordered the attack. Even so, many believe rogue forces acted out of fear of his reforms.

Like his life, his death came without ceremony. At the time, Japan was changing fast. Ryōma had come to embody that change. To some, he moved too quickly. To others, he stood too far outside control. In the end, he was simply too dangerous.

🌸 Ryōma Becomes a Legend

By dying young, Ryōma escaped the compromises that come with power. In doing so, he became more than a politician or a soldier. He became a legend. His letters and ideas continued to circulate, and his reputation grew after the Meiji Restoration. Writers saw him as a hero. So did reformers and ordinary people alike. He had imagined a different Japan and pursued it with conviction. Without an army and without a title, he still managed to move history.

Today, students learn about Ryōma in school. Actors play him in TV dramas. Statues stand in his honour, including the quiet one here in Tachiaigawa. His path was not built on certainty or strength alone. He moved forward with courage. He refused to be limited by birth or rank. That is the story people remember. That is why he still matters.

🗺 Why This Statue? Ryōma’s Link to Shinagawa

This statue honours Sakamoto Ryōma’s early years in Shinagawa, rather than the fame he earned later in life. In the mid-1850s, Tachiaigawa and its surrounding coastline formed part of Edo’s vital coastal defence. The Tokugawa shogunate established this system to guard against foreign incursions during a time of growing uncertainty. At around twenty years old, Ryōma served here as a junior samurai from the Tosa domain. He was posted to this frontline position at a critical moment in national history.

Tosa’s lower residence stood nearby. So did the Hamakawa Battery. These records show the area’s military role. For Ryōma, this place marked a turning point. He faced the clash between samurai duty and national change. He began to picture a Japan beyond feudal rule and closed borders.

🌱 A Turning Point Begins Here

The statue stands here for that reason. It marks the quiet years before he became famous. The community chose to honour the young man on guard. He could not yet see how far his path would lead.

📍 The Statue: A Place Chosen with Purpose

Unveiled in November 2010 by the Tokyo Keihin Rotary Club, the bronze statue stands quietly at the edge of Kitahamagawa Children’s Park, close to the Tachiaigawa River. Its location holds deep meaning, as it sits within the former grounds of the Tosa domain’s lower residence. This placement directly connects to Ryōma’s early service at the nearby Hamakawa Battery during the Tokugawa shogunate’s efforts to defend Edo Bay.

To symbolically link Ryōma’s birthplace in Kōchi with the capital, the statue includes bronze fragments from the restored Katsurahama monument. While it draws visual inspiration from that original, this version is unique. It shows Ryōma at around twenty years old, dressed in worn travel clothes and simple straw sandals. His expression is calm and reflective, capturing a sense of thoughtfulness rather than heroic display.

The statue stands on a modest stone pedestal. Its surroundings are quiet and open. Trees cast soft shadows across benches. Nearby, the sound of passing trains and children’s voices adds life to the scene. The space invites visitors to pause. It encourages them to see not just a famous name, but a young man in the middle of change.

🌟 Ryōma in Popular Culture

More than 150 years after his death, Sakamoto Ryōma remains one of Japan’s most beloved historical figures. His story continues to resonate across generations. As a low-ranking samurai who challenged the system and dreamed of a new Japan, Ryōma still feels relevant today. He appears in television dramas, novels, manga, and video games. His image, often shown in traditional clothing with one hand on his sword or eyes turned to the horizon, is instantly recognisable across the country.

One of the most influential portrayals of Ryōma came from author Shiba Ryōtarō. His epic novel Ryōma ga Yuku (Ryōma Goes Forth) helped to establish Ryōma as a national hero. Shiba portrayed him not only as a revolutionary, but also as a witty, humane, and forward-thinking man. The novel later inspired NHK’s long-running Taiga drama series. As a result, this version of Ryōma continues to shape how he is remembered today. He is often seen as someone who looked forward while others clung to the past.

Today, Ryōma’s legacy lives on in many forms. Tourism campaigns in his native Kōchi, wax statues in museums, and school materials all keep his memory alive. For many people in Japan, he represents more than history. He stands for potential. His name is often linked to critical thinking, social reform, and bold action. In popular culture, Ryōma is not just the man who helped bring down the shogunate. He is a symbol of transformation and belief in a better future.

🧭 Visitor Information

Address: Kitahamagawa Children’s Park, 2 Chome-25-22 Higashioi, Shinagawa City, Tokyo 140-0011

Opening hours: Open 24 hours

Admission: Free

🧭 Where is it?

| what3words | ///submits.meaning.toast |

| latitude longitude | 35.5979131, 139.7385119 |

| Nearest station(s) | Tachiaigawa Station (Keikyū Main Line) |

| Nearest public conveniences | Local convenience stores or nearby station |

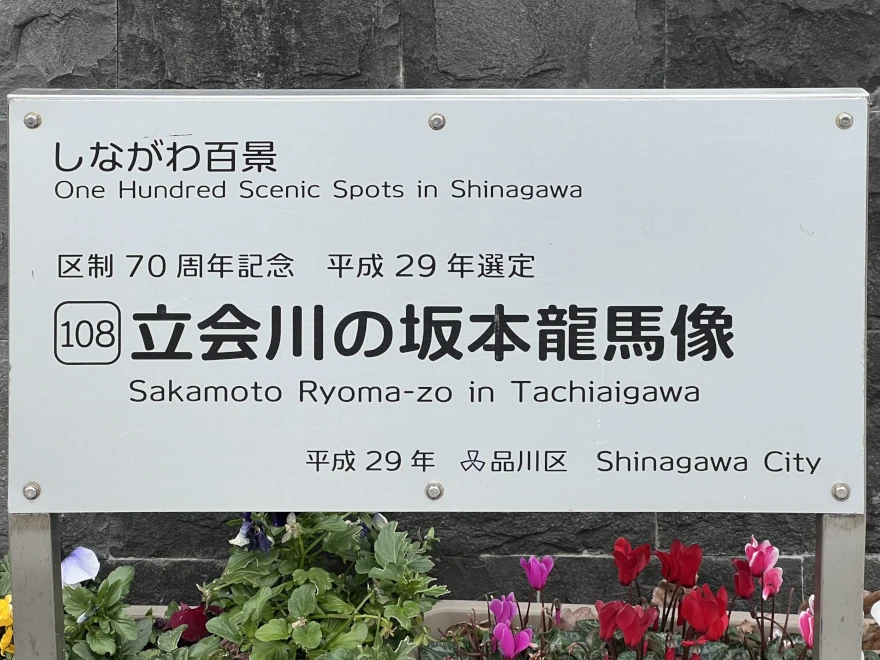

Show me a sign.

Right in front of the statue.

Withervee says…

If you were not paying attention you would miss it. There are a couple of signs, in Japanese, indicating that it’s a statue of somebody.

💣 The Cannon and the Coast

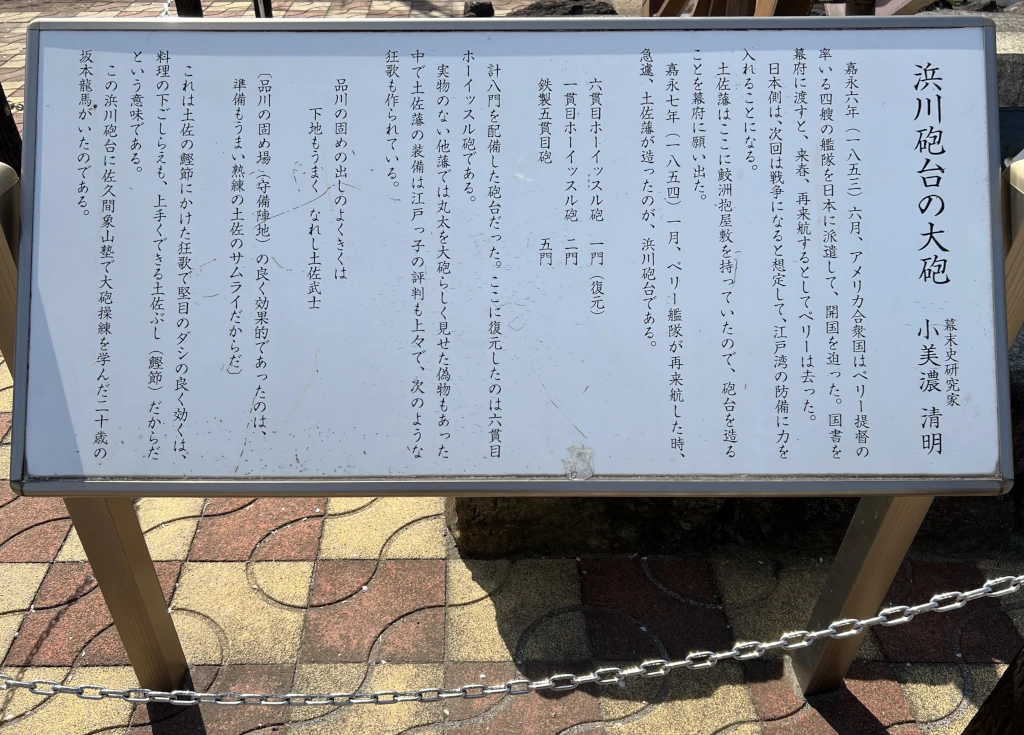

At the nearby Shinhamakawa park there is a cannon. The “Hamakawa Battery Cannon,” restored and installed in Shin-Hamakawa Park in 2015, is a life-size replica of a “30-pound, 6 kanme (約30ポンド6貫目) howitzer” (30ポンド6貫目ホーイッスル砲).

Nearby is an explanatory sign written by Bakumatsu historian: Omino Kiyomei (小美濃 清明)

In June 1853 (Kaei 6), the United States sent Commodore Perry’s fleet of four warships to Japan and demanded that the country open to foreign trade. When the ships arrived again the following spring, the Tokugawa shogunate assumed war was possible. As a result, it strengthened coastal defences around Edo Bay.

The Hamakawa Battery was built as part of this effort. The land here belonged to the Tosa domain, which already owned a whaling lodge on the site. Because of this, the shogunate asked Tosa to construct and manage the gun battery.

In January 1854, when Perry’s fleet returned to Japan, the Hamakawa Battery was completed. It was one of several emergency coastal fortifications designed to protect Edo.

Details of the cannons

The battery was equipped with the following guns:

- Six 24-pound howitzers

- One 6-pound howitzer

- One 12-pound howitzer

- Five iron cannons

In total, five firing embrasures were built.

These were howitzer-style cannons, designed for high-angle fire. Some of the weapons were functional, while others were non-functional display cannons intended to intimidate foreign ships.

The sign notes that the equipment used by the Tosa domain was considered superior to that of other domains. Contemporary accounts praised the quality of Tosa’s artillery.

Why Tosa performed well here

This effectiveness came from:

- Strong preparation

- Intensive training

- Experience gained at Shinagawa’s coastal guard posts

Tosa people were known for their direct, unpolished style, comparing it to strongly seasoned fish dishes. This bluntness, the author suggests, translated into practical military skill.

Link to Sakamoto Ryōma

Sakamoto Ryōma was stationed at this Hamakawa Battery. At around twenty years old, he trained here in artillery handling and coastal defence. This experience formed part of his early military education during the tense years of foreign pressure.

Seen up close, this cannon reflects more than firepower. It marks a moment when Japan faced the outside world and struggled to respond. Ryōma stood beside weapons like this while foreign ships waited offshore. Change did not arrive all at once. It began quietly, during guard duty, observation, and thought.

Site Character

- Lifestyle 生活 (Seikatsu): ❌

- Historical Significance 歴史 (Rekishi): ✔️

- Atmosphere/Natural Features 風土 (Fūdo): ✔️

Who in their right mind would vote for this?

- History nerds

- Samurai lovers

- Introverts

- Philosophers

- Fervent patriots

Further reading

While you’re there…

Take a detour and check out the nearby Hamakawa battery (not a spot) on the way to Shinagawa Hanakaidō for a quiet end to your Ryōma-inspired wander.