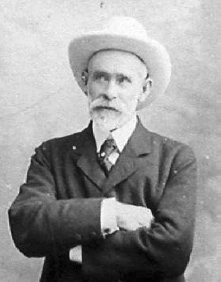

Captain John Mathews James and the Legacy of Zemusuzaka

Captain John Mathews James (1838–1908) may be one of the most fascinating yet least known figures in Anglo-Japanese history. A Cornish sea captain, arms dealer, naval instructor, Buddhist convert, and eccentric resident of Shinagawa, he left a legacy that survives today in the name of Zemusuzaka — the slope he funded and reshaped. While his naval work helped modernize the Japanese fleet, his local contributions literally reshaped the streets of Tokyo.

But his story goes far beyond one hill. From the opium trade and secret missions to Buddhist scholarship and shipbuilding, James’s life was full of strange turns. If Shinagawa has ghosts, his might be among the friendliest — and most eccentric.

🌊 Born for the Sea (1838–1854)

James was born on 3 November 1838 in Chyandour, near Penzance, Cornwall. Although he would later talk about “naval traditions,” his family had modest roots. His father, Richard James, was a commercial clerk. There’s no solid evidence of a naval background, though one of his older brothers was listed as a sailor.

Still, young John had the sea in his blood. By the age of 15, he had signed on as a ship’s boy aboard a merchant vessel bound for Mauritius. Over the next decade, he crisscrossed the Indian Ocean, sailed to China, and learned how to command men and manage ships.

💼 Into Trade, Arms, and Risk (1854–1866)

In 1862, James appeared in Hong Kong directories as the captain of the steamer Carthage, operated by the British firm Jardine Matheson. This was a time of empire, opium, and opportunity. James thrived in that world, commanding ships between India, Hong Kong, and Japan. Some of them carried opium. Others carried guns. He was known as a firm, even harsh, captain — a trait shaped by years managing tough Malay crews on dangerous waters.

One of his strangest assignments came in 1866. James was hired to pilot a steamer for German trader Ernst Oppert on a bizarre mission: dig up the bones of a Korean prince and hold them for ransom. James helped navigate the ship up Korea’s Han River, but wisely bowed out before Oppert’s grave-robbing scheme went ahead. The plot failed. James’s reputation survived.

⚓ Enter Japan: Sails, Samurai, and Students

By the mid-1860s, Japan was opening up to the world. Domain lords wanted modern navies. James was in the right place at the right time. Through connections with Thomas Glover, he helped sell British steamships to Japanese domains, including Saga, Fukuoka, and Choshu. More than that, he trained their crews, sailed the ships himself, and offered real lessons in seamanship.

In 1869, he oversaw the construction of the Josho-maru — later renamed Ryujo — in Aberdeen. This warship became the first flagship of the new Imperial Japanese Navy. It was a proud moment for James and the beginning of a deeper connection with Japan.

🕵️♂️ Covert Missions and Smuggled Samurai

James also assisted in smuggling Japanese students and reformers out of the country. In 1866, he secretly took samurai like Seki Yoshiomi and Hattori Senzo to Singapore and beyond, helping them escape the restrictions of the Tokugawa regime to study abroad. He braved typhoons, wrecks, and coastal attacks, and built friendships that would last for life.

🏛️ O-yatoi Years: Teaching the Navy

In 1872, James officially joined the Japanese government as an o-yatoi gaikokujin — a hired foreign advisor. He taught navigation, captained training ships like the Tsukuba and Meiji-maru, and helped deliver more warships from England to Yokosuka. And, James became so beloved by his students that they nicknamed him “Kapitan James”.

Occasionally, James was sent on intelligence-gathering missions, including reconnaissance trips to Chinese and Korean naval bases. His value was not just in knowledge — but in boldness and initiative.

📿 From Sea Captain to Nichiren Buddhist

One of the most unusual chapters of James’s life began in the 1880s. He formally converted to Nichiren Buddhism in 1880 at Ryuhonji Temple in Yokosuka. This was decades before figures like Olcott and Blavatsky brought Buddhism into Western fashion. James practiced sincerely, wore prayer beads, translated texts, and attended sermons in Shinagawa temples near his home.

Though he denied being a convert when first asked — perhaps to avoid scandal — his beliefs were well known by the time he began giving papers to the Asiatic Society of Japan on Buddhist rosaries and doctrines. Some foreigners mocked him. The Japanese took him seriously.

🏡 The Shinagawa Years and Zemusuzaka

James made his home on a steep hill in Shinagawa, then a quiet area of rice paddies, temples, and shipping lanes. He built a grand house with a sea view and hosted an eclectic crowd — nobles, naval officers, artists, Buddhist monks, journalists, and Theosophists. His guests included heavyweights like Ernest Fenollosa, Joseph Heco, and Colonel Olcott.

But James didn’t just host parties. He improved the neighborhood. The hill to his house, known as Sengenzaka, was steep and dangerous. James paid out of pocket to lessen its grade. In return, the townspeople renamed the slope Zemusuzaka, a phonetic twist on “James.” The name survived WWII renaming efforts and lives on today as one of Shinagawa’s most distinct hills.

🪦 Last Years and Final Legacy

James retired from formal government work in 1889, though he stayed active as a consultant for British shipbuilders. He was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun three times, received an imperial honorary court rank (sonin), and remained active in Tokyo’s public and naval circles.

In his final years, he battled illness and suffered the loss of his house to fire. He died in 1908 after receiving a message of sympathy from the Meiji Emperor. His ashes were taken by a Nichiren priest to Mount Minobu, where they were interred near the grave of Nichiren himself — a fitting resting place for Japan’s most unlikely Buddhist sea captain.

📍 What Remains

James left no children. His wife, Kataoka Yaeko, remains largely unknown in records, and their adopted relative Kataoka Etsujiro faded from view. But two things remain in Tokyo today that keep his memory alive: the Meiji-maru lightship he once commanded, preserved on the campus of the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology — and the slope that still bears his name: Zemusuzaka.

James’s contributions were practical, spiritual, and symbolic. He modernized Japan’s navy, introduced new ways of thinking, and treated Buddhism not as fashion but as faith. He also helped a neighborhood breathe a little easier — quite literally — by fixing a road. That slope may be steep, but it’s his, and it still carries his story.

🌿 “Shinagawa James” — A Life on Many Currents

He was called many things: Kapitan, Shinagawa James, Monkey James. He was at once a sailor and a scholar, a sinner and a seeker. His life ran parallel to the rise of modern Japan — and helped shape it. He deserves more than a footnote. He deserves a walk up Zemusuzaka, with a pause beneath the pagoda trees, and a nod toward the sea.

Much of the information above is taken from “Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits, Vol. VIII” and the chapter on John Mathews James by Sebastian Dobson.